I have no special talents. I am only passionately curious.

Albert Einstein

Curiosity is the engine of achievement. It drives our knowledge forward. It tempts us into dangerous and forbidden waters. And it is the foundation of innovation. Steve Jobs took a calligraphy class when he was a student at Reed College. He then hung out for another 18 months, studying the subject like a Buddhist monk. He later credited calligraphy with inspiring Apple’s typography.

In France, Henri Matisse and Pablo Picasso studied African sculptures. They observed the highly stylized treatment of human faces. Then they combined it with Impressionist painting styles. The result was Cubism—colorful palettes, flatness, and interlocking planes of simple geometric shapes. It revolutionized the modern art scene.

Whether it’s said by Jobs or Picasso, original thinkers are overrated. “Good artists copy; great artists steal.”

What is curiosity?

Curiosity starts with an inquisitive mind. We’re all born with it. Infants prefer to look at new pictures, not familiar ones. Preschoolers play longer with a mechanical toy when it’s harder for them to learn how it works. A curious mind prefers diversion and unplanned excursions. Curiosity is unruly. It disdains approved paths.

As we grow older, some still enjoy mentally challenging activities more than easy ones. These people don’t take shortcuts. They prefer to take the scenic route when trying to make sense of the world. It’s a personality trait that psychologists call the “need for cognition.” It measures how much people love to think deeply, regardless of monetary reward. Are you ready to find out yours?

Try answering the following questions with “true” or “false.” There are only 18 items. Don’t overthink them and be truthful with yourself. The quiz should take no longer than three minutes to complete.

- I prefer complex problems to simple ones.

- I like being responsible for situations that require lots of thinking.

- Thinking is not my idea of fun.

- I would rather do something that requires little thought than something that challenges my thinking abilities.

- I try to anticipate and avoid situations where I might have to think deeply about something.

- I find satisfaction in deliberating long and hard.

- I only think as hard as I have to.

- I prefer small, daily projects to long-term ones.

- I like tasks that require little thought once I’ve learned how to do them.

- The idea of relying on thought to make my way to the top appeals to me.

- I really enjoy a task that involves coming up with new solutions to problems.

- Learning new ways to think doesn’t excite me very much.

- I prefer my life to be filled with puzzles that I must solve.

- The notion of thinking abstractly is appealing to me.

- I prefer a task that is intellectual, difficult, and important to one that is somewhat important but does not require much thought.

- I feel relief rather than satisfaction after completing a task that required a lot of mental effort.

- It’s enough for me that something gets the job done; I don’t care how or why it works.

- I usually end up deliberating about issues even when they do not affect me personally.

Check if you’ve answered “true” to more than five of these questions: 1, 2, 6, 10, 11, 13, 14, 15, and 18. Now check if you’ve also answered “false” to more than five of these: 3, 4, 5, 7, 8, 9, 12, 16, and 17. If so, chances are that you have a higher need for cognition than the average person. It means that you intrinsically enjoy cognitively challenging activities.

Why is having a hungry mind is important?

We’re all forecasters. We all want to know what’s going to happen next. When curiosity is triggered, we’re less likely to fall prey to confirmation bias, which occurs when we seek out information that supports our current beliefs and ignore evidence suggesting that we’re wrong. Curiosity counters that tendency because it leads us to generate alternatives.

Without being curious, we can’t learn. Even when we try, we learn the wrong lesson.

“I am 46. I’ve been married for 22 years and we have 3 kids. … I buy more books than I can finish.” That was how Satya Nadella introduced himself in an open letter to Microsoft employees when he was appointed CEO in 2014. “I sign up for more online courses than I can complete. I fundamentally believe that if you are not learning new things, you stop doing great and useful things,” he said.

Nadella was promoted at a time of setbacks. Before him, product flops were common at Microsoft—Zune, Vista, Kin, and Bing. The software giant took a $900 million write-down on unsold Surface tablet inventory. It was losing out to Amazon, Apple, and Google in music players, e-readers, and smartphones. And the PC market was in decline.

Nadella’s letter didn’t mention his predecessor, Steve Ballmer. It emphasized Bill Gates instead. Nadella wouldn’t let profitability alone define his career. Curiosity and hunger for knowledge defined him, he wrote.

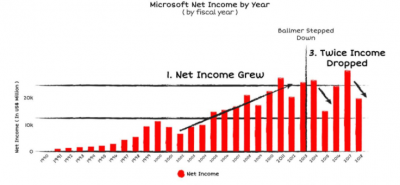

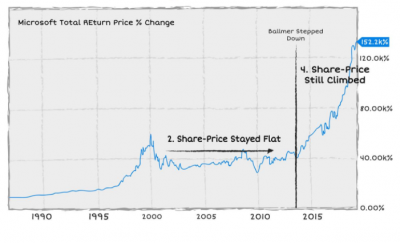

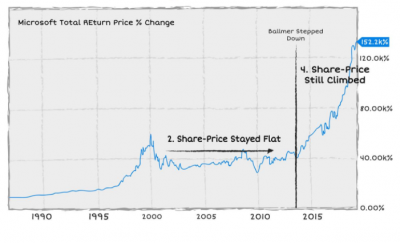

Shareholders welcomed the news and the tech press lauded the move. Microsoft’s stagnant share price shot up 7% after the announcement that Ballmer was stepping down.

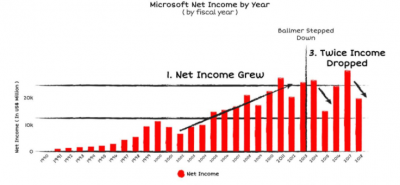

Some said the disdain for Ballmer was unfair. No company, they argued, could have foreseen Apple’s gains in the mobile space. And Ballmer was the CEO who had tripled Microsoft’s annual revenue from $23 billion to nearly $78 billion. He had introduced best-selling products like Windows 7, which ruled the PC market for almost a decade. They said it was the financial market being unfairly punishing. Back in December 1999, Microsoft’s market cap hit $614 billion. By June 2012, that cap had been reduced to $249 billion. During the same period, Apple’s grew from $4.8 billion to $541 billion.

It’s hard to predict share prices, Ballmer tried to explain. “At the end of the day, they have to have something to do with profit.” But a look at Microsoft’s earnings in relation its share price tells us that’s the wrong conclusion

Growth prospects, not profits, decide a company’s share price. Profitability is the consequence of decisions made in the past. Because the stock market is forward-looking, it’s futile to trumpet rising profits without showing innovation. That’s why people were tired of Ballmer. His narrow view of how things work led him to draw the wrong conclusions all the time.

If only closed minds came with closed mouths

Three years after stepping down, Ballmer still didn’t understand what he had done wrong with mobile OS. He couldn’t grasp why Microsoft had lost the battle against Apple and Google. The ex-CEO made that point clear at a conference in 2017, when he said Microsoft should have produced its own hardware. This was a way to defend his ill-fated acquisition of Nokia. It only revealed his envy of Apple. He couldn’t accept nor understand the logic of Google’s Android: Software licensing is out. Subscription is in. Everything else is in the cloud. In 2015, Microsoft wrote off $7.6 billion because of the Nokia acquisition. It laid off 7,800 employees, mostly in its phone business, which had become “immaterial.”

No one denied Steve Ballmer had been a great partner to Bill Gates. Gates could think about the future from the stratosphere because Ballmer was the tough obsessive who kept the show on the road. But when he took over as the CEO, Ballmer continued to play the salesman who focused on the company’s bottom line. He once ran to find Yang Yuanqing, the head of Lenovo, at a Microsoft event, yelling at his handler, “Just tell me where he is!” Lenovo is the world’s No. 1 PC maker, and a huge Microsoft customer. Grasping his client’s hand and earnestly talking him up, Ballmer looked like he was in his element—a veteran salesman with a beaming smile. He laughed and clapped during the several-minute conversation. He placed his hand on Yuanqing’s shoulder before embracing his hand once again and departing.

But when asked if Ballmer was ever involved in any product decisions, one longtime designer said a flat “no.” Another added, “Not at all.” Yet another said, “I don’t think Steve could even spell the word design.” Unlike Steve Jobs, who was involved in every aspect of product launch, Ballmer was never hands-on. Nor was he much of an innovator. He simply wasn’t interested. He had no curiosity about an area that needed his attention as a CEO.

Can I feed my mind?

The lack of curiosity among leaders can be comical. Michael Eisner, the former Disney CEO, never bothered to understand Pixar when Steve Jobs led it, even though Disney and Pixar both created animated films. And it was under Eisner that Disney began to distribute Pixar’s movies: Toy Story, Monsters Inc., Finding Nemo, and The Incredibles. This was also a time when Disney’s own animation studio gradually sank into irrelevance. All it released were tepid bummers or outright disasters. There was Fantasia 2000, The Emperor’s New Groove, Lilo and Stitch, Treasure Planet, Brother Bear, and Home on the Range. None were memorable.

Steve Jobs recalled thinking that the CEO of Disney should be curious about Pixar’s success. But Eisner visited Pixar for a total of about two and a half hours over twenty years. He was only there to give little congratulatory speeches. “He was never curious. I was amazed,” said Jobs. The worst thing, to his mind, was that Pixar had already reinvented Disney’s business. It turned out great films one after the other while Disney turned out flop after flop. “Curiosity is very important,” Jobs said.

So how can we make ourselves more curious? What should we do if our “need for cognition” is lower than average? Can we rouse ourselves with a strong interest in important topics?

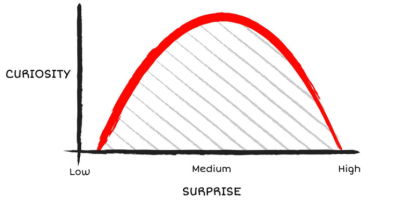

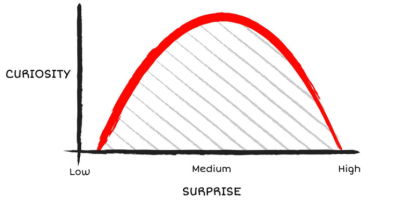

George Loewenstein, a professor at Carnegie Mellon, gave an answer to this question in 1994, in a classic paper called “The Psychology of Curiosity.” Curiosity is simple, he wrote. It comes when we feel a gap “between what we know and what we want to know.” This gap creates an emotion. It feels like a mental itch, a mosquito bite on the brain. We seek out new knowledge to scratch the itch.

What that means is that that curiosity requires some awareness. We’re not curious when we know nothing about a subject. But as soon as we know even a little bit, we want to know more.

To get this process started, Loewenstein suggests, we should “prime the pump”—give ourselves some intriguing but incomplete information.

Newer research shows that curiosity does indeed increase with knowledge. The more we know, the more we want to know more. That’s why field trips, or learning expeditions, can be powerful prompts for senior executives. They unleash curiosity in otherwise all-too-busy managers. Field trips combine visits, workshops, meetings with experts, and tours of start-ups or even competitors. They can happen on the other side of the globe — think Shanghai, Nigeria, Silicon Valley or Tel Aviv — or they can be right next door. Think co-working spaces and shop or factory visits. Expeditions are most effective when they let us observe places, practices, and people other than those we’re familiar with. They break our usual routines and take us out of our comfort zones. And neuroscientists agree that this is the most effective way for us to learn.

How curiosity prepares the brain for better learning

One interesting neurology study came out from the University of California, Davis. Using functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI), Matthias Gruber and his colleagues had students answer a series of trivia questions while inside a brain scanner.

After reading each question, the subjects were told to silently guess the answer. They then indicated their curiosity about the correct answer. Did they not care what the answer was or were they “dying” to know? Next, students would see the question presented again, followed by the correct answer. Tha was it.

The first thing the scientists found is that curiosity follows an inverted U-shaped curve. We’re most curious when we know a little about a subject, but not too much, and we’re still not certain of the answer. This supports the information gap theory of curiosity we saw above.

But here’s the wrinkle. In the moments when the question was first asked, if the subject showed a high level of curiosity, the brain would increase activity in three areas. The brain revved up in the ventral tegmental area and the nucleus accumbens. These are the two regions transmitting dopamine, the happy molecule responsible for the sensation of pleasure and reward. But a third region, the hippocampus, which is involved in the creation of memories, also activated.

During moments of peak curiosity, our brains aren’t just primed to learn the answers to trivia questions. They also remember anything surrounding those moments better. Gruber’s team tested this hypothesis further. He presented unrelated faces right after the volunteers were “primed” to be curious. He wanted to know how much people could remember those faces months after the experiment. The result? People could remember more of the information paired with interesting trivia questions than boring ones.

All these things suggest a “thirst for knowledge” is more than metaphorical. Knowledge has a reward value for the brain. When we feel the itch because of what we already know, we’ll enjoy learning more. And we’ll remember it better too. Learning favors the prepared brain. Deprived of curiosity, we end up with impoverished minds.

Prompting Yourself, Every Day

You know these people, or maybe you’re one of them. They’re the kind of people who simply couldn’t put up with corporate nonsense. They are the kind of people who want work to be play. But meaningful play. Henri Matisse. Pablo Picasso. Steve Jobs. Albert Einstein. They are fighting against conformity and drudgery. Whether they know it or not, they prompt themselves to be curious, every single day.

Stay healthy,

Author : Howard Yu

Professor, Author, Keynote Speaker

LEGO Professor of Management and Innovation at IMD Business School

https://www.howardyu.org/